A PDF version is available here.

Back in 2024, I joined the International Bridge Group for a wonderful trip to Avignon. Previous Bridges of the Month from that trip are Pont d’Avignon and Pont Julien. I’ve let nearly 18 months pass, and haven’t yet featured Pont du Gard. Better late than never!

This photo was with my phone’s wide-angle mode. The quality isn’t great, but it captures the drama.

Delightful details abound, such as this at the crown of one of the tier 2 arches.

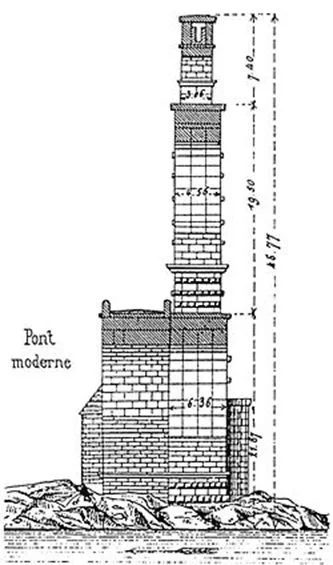

The lower tier was widened in the 19th century to carry a road (now mainly a tourist footpath): the “Pont moderne” in Léger’s 1875 drawing (left). The construction joint is clear in the photo above, the widening is the smoother stone on the far side..

Notice that the arches of the lowest tier were built in four strips, those of the second in three. Each strip is of full thickness voussoirs, with no interlocking bond. The same style is seen at Pont Julien, of similar age, and Pont d’Avignon, much later.

Notice the gravel on the ledge in the near span here: this valley sometimes carries water across the full width.

The top four courses of the near cutwater have been added or replaced, as has much of the nearest arch. The two course corbel in the second span was provided to support the timber centre during construction. The courses below this point can be placed more conveniently with no formwork in the way. The same approach was used in the widening.

The original piers were built with normal bonded masonry. In the second pier above, the ledge appears to be lower and below the arch springing, but the stones are bonded up to the same level as in the near span.

In the second tier (left), the voussoirs up to the corbel are of varying length. This doesn’t look like a full bond as Léger drew it, just some overlap here and there. Perhaps this was not out of concern for robustness, but to make best use of stone where the construction method didn’t require equal length voussoirs.

Above the corbelled courses, the arch is built strictly in strips. Bill has suggested that this enabled construction on relatively slender piers with a minimal number of narrow timber centres.

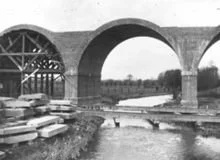

The Victorians typically built viaducts with a moving “front” of three spans. The centres could be removed from the rear span only once masonry backing was complete to considerable depth in the valleys between the arches (photo right). These rear centres were then hopped round to the front, and the next arch begun. The thrust from a full arch with no centring in place on a pier is non-trivial, and likely to topple the pier. The set of at least two centred spans (in the temporary condition while the third centre is being moved) locks creates a stable “abutment” to protect the pier at the leading edge.

The thrust from a single strip of a third or a quarter the full width, in contrast, exerts thrust in proportion to the width. By advancing strips of arch in a wedge formation, the piers are protected without tying up two full spans worth of centring.

There has been considerable repair work, with many voussoirs replaced to part depth.

Repairs to the upper, aqueduct tier have been more extensive. I suppose the small-block wall is repair.

The erosion to the voussoirs in this span (right) is unusual - compare it with the spans just visible in the photo above left.

I think I was as excited by the lime scale build up as by the structure itself. The spring water that supplied the aqueduct has very high dissolved carbonate content. While the aqueduct was in use, it required constant maintenance. When maintenance was neglected the flow was gradually restricted.

The construction of that curve (on the cliff top to the south of Pont du Gard) is fun, making the most of natural rock and using wedge shaped stones to form the curve.

Following the aqueduct to the south, we come to a bridge over a small valley, from Google Maps perhaps called Pont de Valmale, which gives a great view of internal construction: rubble concrete with a pretty ashlar skin. This was very well built, with much more mortar than I would expect to find in most mass masonry.

Further south again, another significant valley was crossed by the Pont de la Combe Roussière (below left). This was another significant structure, though little now remains.

A spectacular place!